Have His Carcase is the seventh of the eleven Dorothy L. Sayers Lord Peter Wimsey mystery novels, and the second of the quartet that includes Harriet Vane. I’m reading the eleven mystery novels in publication order with a small group. Some of us are re-reading; others are reading for the first time. With every book, this one included, the consensus is that whatever we’ve read latest is the best, most entertaining, most accomplished. It could be recency bias, or that Sayers was growing into her power as a writer both in plot and style. It will be interesting to see how the group reacts to the next three books, all of which have been claimed to be the best or the masterpiece by someone or other.

Carcase is the English spelling of the American word carcass, pronounced the same and meaning the body of a beast, often that has been slaughtered. The book opens with a cheerful and relaxed Harriet, in much better spirits than when we last encountered her in Strong Poison. The arch, ironic tone reminded me of Austen’s opening to Pride and Prejudice:

The best remedy for a bruised heart is not, as so many people seem to think, repose upon a manly bosom. Much more efficacious are honest work, physical activity, and the sudden acquisition of wealth. After being acquitted of murdering her lover, and indeed, in consequence of that acquittal, Harriet Vane found all three specifics abundantly at her disposal; and although Lord Peter Wimsey, with a touching faith in tradition, persisted day in and day out in presenting the bosom for her approval, she showed no inclination to recline upon it. (9, Avon 1968)

Harriet is on a walking holiday. It was not uncommon in England then for a woman to be traveling alone, while in the United States, one of the tensions of the much more recent bestseller Wild by Cheryl Strayed, is precisely that danger. She carries a light pack,

not burdened by skin-creams, insect-lotion, silk frocks, portable electric irons and other impedimenta beloved of the “Hikers Column.” She was dressed sensibly in a short skirt, and thin sweater, and carried, in addition to a change of linen and an extra provision of footwear, little else beyond a pocket edition of Tristram Shandy, a vest-pocket camera, a small first-aid outfit and a sandwich lunch. (10)

(I find it curious, again, to contrast the fictional Harriet, with her light pack and single outfit with only a change of linen, to Strayed’s real-life expensive and heavy kit, which she nicknamed Monster, and which significantly did NOT include an extra provision of footwear. Then again, Harriet is rich and staying in English hotels, while Strayed was poor and camping outdoors in America. But both are seeking to leave the memory of a bad ex behind.)

I’ll try to summarize the book from here, but it’s not going to be easy. The book is long, its plot deliberately labyrinthine, and its cast of characters substantial. One of the many delights for me of this book is how deftly and yet with seeming lack of effort Sayers creates a whole seaside universe and beyond, richly furnished with sympathetic and complex characters. I was going to say “peopled” but edited it because one of the great characters is a traumatized horse. (Oh, dear, I am really going to have to look into this fanciful compare/contrast of HHC and Wild, aren’t I?)

Harriet eats her sandwich on the beach, dozes off, wakes to a sudden noise, and then discovers a man’s body on a nearby rock, with his throat cut and the blood still hot and liquid. But the tide is coming in, so Harriet works fast, takes pictures, grabs what she can from the body, including a shoe, then hustles off to try to raise an alarm. But everyone is out fishing, so she takes a long time, and thus puts herself under suspicion–so much for the entirely acquitted, now the whole incident she was trying to forgot is regurgitated in the press. She tries to get ahead of it and claim her notoriety. She and the reader spend a good deal of the book thinking she’s succeeded, but we later learn that’s not quite true in a five page passage that I’ll get to as soon as I can.

Lest you think this is going to be Harriet’s book. Here is where I wish I had Tara Menon’s direct dialogue counter (she researched Victorian literature to demonstrate who had the most power in the books shown by the data of dialogue) so I could directly compare Harriet’s number of words to Peter’s and see who wins. Drat, I really keep setting myself up for research projects/papers, don’t I?

Guess who shows up the morning after?

“Good morning, Sherlock. Where is the dressing gown? How many pipes of shag have you consumed? The hypodermic is on the dressing room table.”

“How in the world,” demanded Harriet, “did you get here?”

“Car,” Lord Peter said briefly. “Have they produced a body yet?” (40)

Peter does know how to make an entrance.

The body was Paul Alexis, a local gigolo and hired dancer at one of the resorts. An older woman begs Harriet to listen to her, and says that she was engaged to Paul, and that he would never have killed himself. It must have been Bolshevik’s, because Paul was exiled Russian royalty. But how could it be murder? It took place on a deserted beach and there were no footprints in either direction, and with all that fresh blood, Harriet had to have just missed the murder. The novel unfolds in a zillion different directions into an homage, or is it a satire, of a Ruritanian novel, like The Prisoner of Zenda, that turns on super complicated plot details about inheritance and identity. Over the course of this chonky book (my mass market paperback has 350 pages, one trade is 450, and yet another is 476!):

Peter flatters Harriet into buying a claret dress, then annoys her when he wants to talk mystery and not how fetching she looks in it.

A creep tries to assault Harriet and she successfully defends herself with a big hat.

The private dancers become three dimensional. There is a complex trail of the razor used to cut Alexis’ throat, and the sad drunk who owned it. Paul’s ex lures Peter to her room, but he leaves with his virtue intact, clutching valuable intel. He accidentally auditions for a play and wins a part. As usual, he’s that perfect. People have double identities and multiple alibis. Theater people are involved. Cars, too. A traumatized horse. And smack in the middle of all this nonsense is a powerful five page section of Peter and Harriet trying to get honest with one another, yet still holding things back.

Peter doesn’t tell her that her brazening to the press about the body only worked because Sally Hardy warned him what was coming, and Peter interfered with the press. Harriet has not and will not admit to her growing affection and attraction, because of the gross debt she owes him for saving her life in Strong Poison. Harriet bursts into tears and says things are dreary. Peter throws himself to his knees in an interestingly subservient physical position then offers her a handkerchief between lines: “Have this one, darling. It’s much larger and quite clean.” They’re interrupted by the telephone, and never quite get back to this same place of honesty and vulnerability. They even solve the crime after puzzling out an extremely tedious code, and the end is a rush, in which we’re not certain if anyone is going to be arrested or successfully tried and then Peter and Harriet merely go off to dinner together and, the end?

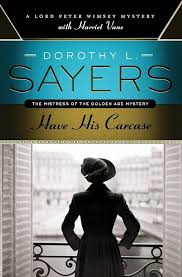

The whole thing is complicated and bonkers and I found it thoroughly entertaining except for the part when they solved the code, which I skimmed. And I loved it most because of the centrality of Harriet who is trying to figure out how to be a writer and a person in the wake of her trauma, and in spite of the love bombing of Peter, who at least is listening to her and politely taking no for an answer. It was my favorite of the books to this point in the series. I love the cover of the copy I read, which has a bloody corpse atop a rock with a fashionable woman in the foreground. The range of covers over the years is fun to see, and while the abstract of the Penguin green is quite excellent, I think the others all have a lot going for them (but also some weird gaffes. Like, that purple outfit is neither what Harriet was hiking in nor the claret dress, nor the outfit she used as defense with the handsy presumptive cad. It’s also one of the most performatively gendered of the Wimsey books, with men and women doing an intricate dance and with lots and lots of subterfuge and strategy, not just in the mystery but in the relationships as well.

My favorite side character is once again a capable young person who gets insulted by someone else at work and yet knows better than they do. In Five Red Herrings, it was a woman at the mechanic’s office. Here, in a similar role, it’s a boy apprentice at the auto shop. I have a great deal of empathy for Mrs. Weldon, as well as for Antoine the dancer, yet I’m not sure Sayers did. She wrote some really cruel things about these characters that struck me as possibly being what she thought in real life, and not just what she put in her characters’ mouths.

In thinking about my perpetual question, which book to recommend to someone new to the series, I think there’s a good argument to be made for this one. It’s got a good plot, side quests for Harriet and Peter, and good character development. It’s a good Harriet book and to me, Harriet is the ne plus ultra ingredient of the series. Apparently she had a lot of haters back in the day, but as we continue to trudge into this 21st century, I don’t think the series could be relevant without her.

The current American editions are put out by Bourbon Street Books, a division of Harper Collins. They feature dull black-and-white photographs that say little about the book, though this one does at least hint at what Harriet’s ridiculous defensive hat might have been.

This edition has a an introduction by mystery writer Elizabeth George, which is so general as to be rather disappointing. What I’d wish for is an afterword, so it doesn’t spoil the book, by a particular author, about each particular book. I do like this comment:

Times have changed, rendering Sayers’s England in so many ways unrecognizable to today’s reader. But one of the true pleasures inherent to picking up a Sayers novel now is to see how the times in which we live alter our perceptions of the world around us while doing nothing at all to alter the core of our humanity. (Bourbon Street Books, ix)

Better, I think, would have been the afterword by John Curran, included in several of the other Bourbon Street titles, in which he owns, contrary to popular opinion:

But my favorite Sayers novel remains Have His Carcase (1932). While on a walking holiday to recover from the broken heart sustained before and during Strong Poison, Harriet Vane discovers a dead body in the pool of blood, as a result of throat-cutting, on the beach at Wilvercombe With admirable sang-froid, she searches the corpse, takes photos, collects evidence, and walks four miles to raise the alarm, after which she calls a newspaper and dictates–no mobile phones or laptops–her story. Is it any wonder that Lord Peter loves this woman? And surely these opening chapters bear out P.D. James’s contention that a body found in civilized, peaceful surroundings has a much more powerful and dramatic impact than one found in a back alley. Part of the plot of Have His Carcase is predicated on a piece of now well-known medical lore, and the clues, all eleven of them [he counted? Also, the clues go to eleven?!] are not just mentioned but, in some cases, brought to the reader’s attention again and again. No accusations of cheating can be levelled at the era’s leading advocate of the fair-play rule. But while the detective plot is ingenious, the character’s portraits–middle-aged Mrs. Weldon and her search for love, pathetic itinerant barber Mr. Bright, as well as the doomed Paul Alexis–are masterly. (Bourbon Street Books, 346)

My spouse took an online class on the Wimsey/Vane quartet books this summer with Kara Keeling through Politics and Prose bookstore in DC. Keeling said that even though the body was on a rock in the open air, the puzzle was more like a Locked Room trope, given the details. It looks like they have another Wimsey class coming up in September.

Some additional links:

If you’re a Wimsey nerd like me, check out the podcast As My Wimsey Takes Me. They now have a Patreon!

For more Golden Age mystery podcasting goodness, check out Shedunnit.

There is a BBC adaptation staring Edward Petherbridge and Dame Harriet Walter. You can seek it out used on DVD or watch it on Youtube. My husband fell asleep anytime he tried to watch it. I like it, but it is not propulsive.

For each of the books, Peschel Press has an annotation, including Have His Carcase.

You can also check out the Dorothy L Sayers Society, which has excellently detailed but rather hard to navigate notes for the series.

Martin Edwards, the crime novelist, has written about Sayers extensively in his history, The Golden Age of Murder. Here he is on Have His Carcase and the Petherbridge adaptation.

I hope to post again soon about Murder Must Advertise, the next book in the series.